Backstory

Backstory

by Edward Petherbridge

A little DAB radio with earphones sustained my mind in hospital when the stroke that had put me there prevented me using my right hand to write, or my eyes properly to read. My unsteady walks to the end of the hospital corridor and back, vital steps towards rehabilitation, needed thinking about but were hardly food for thought, and my mind – neither perfect nor seriously impaired – craved food. The BBC World Service with global news and the New Zealand’s Radio National, providing classical music as well as ‘cultural’ talks, filled the void. Then one day over the airwaves came someone declaring that a stroke may disable the synapses that generate regret. It was then that I grasped the surprising fact that regret was not expending any of my very limited energy.

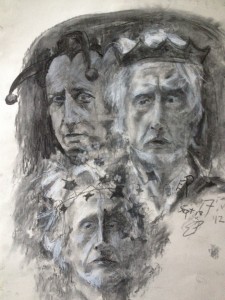

I had been alone but fully conscious when the first stroke happened (the second came two days later and put me out) but luckily that fist time I was able to call for an ambulance and realized ‘at a stroke’ I would not be playing King Lear.

I might have said, ‘Here we go again’ because in 1970 I had been invited twice to play Hamlet, once at London’s Mermaid Theatre and again for the British Council in front of the Phoenician ruins at Baalbek and each chance had been snatched away. The Mermaid suffered a financial crisis and decided to put on a cheaper money-spinner, a four-handed compilation of Noël Coward songs, and as for Baalbek, in a piece of international cultural skulduggery, the Bolshoi Ballet slipped in, offering the Baalbek Festival its services free. The British Council and I were no match.

In another fine twist of fate, ‘my’ Lear had been scheduled to hit a Wellington studio theatre almost precisely to coincide with my old friend Ian McKellen’s world tour in the part with the RSC. I had been relishing the juxtaposition.

All a great pity, but fate has also provided booby prizes on a generous scale. Laurence Olivier gave me the chance to be the very first Guildenstern, supported by a bit-part Hamlet, in the world premiere of Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead for over three years in repertoire at the National Theatre. And when, in 2010, I was harnessed with Paul Hunter in an ill-fated London revival of The Fantasticks (which I see is still running off-Broadway after more than fifty years), Paul and I discovered a rare comic rapport and actually garnered some rave reviews of our very own. More to the point, it was while waiting to go on one night, underneath the stage as the tatterdemalion old stager and his ‘Fool’, that the seeds of something very special were sown. We had to negotiate a ladder and a tunnel and something resembling an S-bend; Paul remarked that the trouble with our entrance was it was not a precise science. On this particular night I said to Paul, who had learned about my NZ Lear debacle, ‘Do you think we could do a two-man version of King Lear for the Edinburgh Festival?’ And Paul said, ‘I think there is a more interesting show to me made about your NOT doing King Lear.’

Months passed. We occasionally met for coffee or a drink to discuss the mooted project and had two short, rather indeterminate workshops after which Paul still had faith and I, merely hope. It was a good move when Paul suggested that the first British actress to play King Lear should join us in devising the show.

Somebody asked the other day what I thought was a rather hifalutin question: ‘What colour would you say your show is?’ I have thought about it and I see it as white with areas of off-white, really because of the set which Michael Vale designed for us to work on from day one of the rehearsals. Not to be hifalutin at all, I would make the scientific point that white contains every imaginable colour; it is only a question of refraction to see them. But have you ever wondered at plants, living in the same patches of grey earth, managing to produce, especially at this time of year, their astonishingly glorious range of colours?

Improvising to create a show in true colours is not, it would seem, a precise science. It is made up of faith, hope and certainly charity and, of course, a sense of humour, the seriousness of comedy. This result has become a precious possession, and to think it all stemmed from that moment in a dark Wellington hotel room when laughter was the furthest thing from my imperfect mind.