ART AND REVOLUTION

As the centenary of the October Revolution approaches, I’m reminded of my research visit to Moscow in the summer of 1984 when I made this diary entry:

My stroll up to Red Square started with a daunted look at the 50th Anniversary of the October Revolution Square. What did they pull down to celebrate the anniversary with this agoraphobic space across which little dots of cars speed alarmingly? What looked like a subway entrance turned out to be one, leading right under the square. This is the prelude to Red Square, not a hint of litter, graffiti or urine, not a poster of any description: part of the length mud, part white tiles and fluorescent lighting. I find I am walking behind four youths conversing in deaf and dumb language; they are wearing running shoes and jeans, but one has a very nice T-shirt, moccasins and the latest cut of lightweight trousers. Their movements in conversation are eloquent, dramatic, completely unselfconscious with the expressiveness that can only come of freedom and conviction. A marvellous chest-exploding gesture, like a heart burst, lots of combative gestures. I get halfway to the top of the stairs at Red Square behind them and they notice me, but continue their conversation. Suddenly, the most stylishly dressed boy looks straight at me and simply gestures, ‘Jeans? T-shirt?’ by subtly plucking his own garments between finger and thumb and looking questioningly at me. Having no spares, I shake my head, wondering what they might offer by way of barter. They go on smiling and conversing together.

A closer look at the odd group of onion-domed towers that is St Basil’s Cathedral, the twirly painted flowers on the walls. It has the mystery that all good buildings have – no logic perhaps, but somehow you can’t argue that it isn’t the perfect set of masses. I long to go in, but it is firmly locked. Another time perhaps.

It seems timely to reprise a short film we made a few years ago, a meditation on inner and outer truth, which features some of my photographs from that Moscow trip:

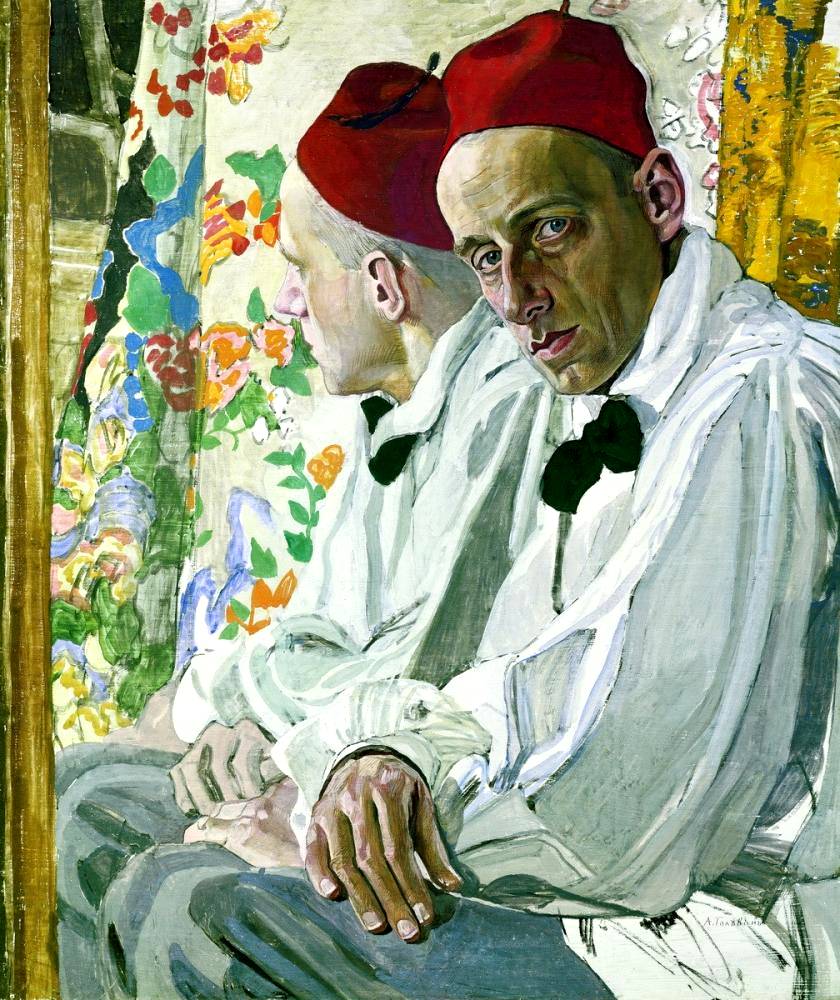

Earlier this year I had two very different encounters with the revolutionary days of 1917. The first was the major exhibition of Soviet art at the Royal Academy which was, by turns, dismaying and impressive. There was a marvellous portrait of the theatre director Meyerhold who invented a system of actor training called Biomechanics. It was not the famous one of him in white tie and tails and in contorted Biomechanical pose, but relaxed in an almost pierrot outfit with a mirror and floral screen in the background – painted in that fateful year 1917.

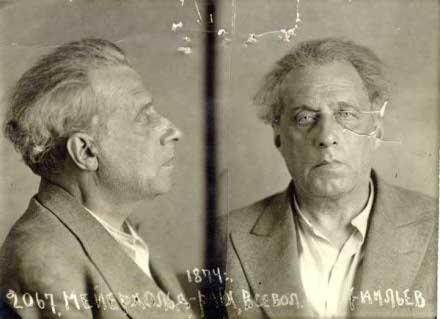

There were also sad, stilted bits of grainy footage of people in soviet shorts performing his Biomechanical exercises. The last things I glimpsed as a I left the exhibition were black-and-white police photographs of people, ordinary men and women, clerks, post office workers, mechanics, the odd journalist, with captions telling us their names and fates – many shot. Suddenly there was Meyerhold without his tie and, like the others, in profile and facing the camera. Tortured and shot.

Back in 1984 I’d probably passed what had been his flat in Gorky Street; there was a lovely Art Nouveau window up there I remember with sunflowers in the ornate window box.

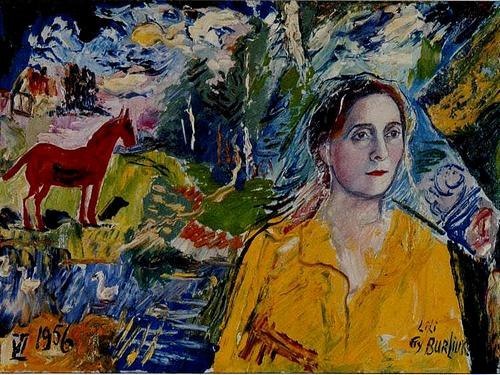

Incidentally, in our NW6 researches, Kathleen and I discovered that the woman dubbed ‘muse of the Russian avant-garde’, Lilya Brik, lived for a time in West Hampstead (which also had the distinction of housing the first Soviet embassy in London). Brik married the Futurist poet Osip Brik and became the muse and mistress of the poet, playwright, artist and actor Vladimir Mayakovsky who was one of the leaders of the Russian Futurist movement. The Moscow apartment of Lilya and her husband was the meeting place for such cultural luminaries as Boris Pasternak, Gorky, Eisenstein and Meyerhold.

My second encounter with 1917 in this centenary year was through the dazzling prism of Tom Stoppard’s play Travesties which had its origins in Stoppard’s serendipitous discovery that James Joyce, Lenin, and Tristan Tzara (the father of Dada) were all living in neutral Zurich in 1917: a comically rich conjunction of expatriates – the high priests of Art, Politics, and Meaningless – working on their separate revolutions. Factually they never met but Stoppard connects them through Henry Carr, a minor official at the British Consulate who played Algernon Moncrieff in an amateur production, by Joyce’s English Players, of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. The action of the play is filtered through Carr’s fallible memory and is a combination of literary pastiche, spoof reminiscence, and competing perspectives of the value of art and the artist to society. At the end of the play, reminiscing about the experience Carr says: ‘I learned three things in Zurich during the war. I wrote them down. Firstly, you’re either a revolutionary or you’re not, and if you’re not you might as well be an artist as anything else. Secondly, if you can’t be an artist, you might as well be a revolutionary. … I forget the third thing.’

My second encounter with 1917 in this centenary year was through the dazzling prism of Tom Stoppard’s play Travesties which had its origins in Stoppard’s serendipitous discovery that James Joyce, Lenin, and Tristan Tzara (the father of Dada) were all living in neutral Zurich in 1917: a comically rich conjunction of expatriates – the high priests of Art, Politics, and Meaningless – working on their separate revolutions. Factually they never met but Stoppard connects them through Henry Carr, a minor official at the British Consulate who played Algernon Moncrieff in an amateur production, by Joyce’s English Players, of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. The action of the play is filtered through Carr’s fallible memory and is a combination of literary pastiche, spoof reminiscence, and competing perspectives of the value of art and the artist to society. At the end of the play, reminiscing about the experience Carr says: ‘I learned three things in Zurich during the war. I wrote them down. Firstly, you’re either a revolutionary or you’re not, and if you’re not you might as well be an artist as anything else. Secondly, if you can’t be an artist, you might as well be a revolutionary. … I forget the third thing.’

-

CATEGORIES

Uncategorized -

DATE

October 3, 2017 -

COMMENTS

Leave a comment

Leave a Reply