AUDIO INTERVIEW

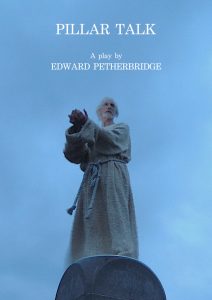

At the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2005, Edward performed his one-man play Pillar Talk about the fifth-century Syrian saint Simeon Stylites, the remains of whose pillar he had visited that year. He subsequently recorded a radio version of the play which will shortly be available for the first time on CD through Brainfood Audiobooks UK. In anticipation of the CD’s release, Edward has recorded a special interview with Brainfood, featuring questions elicited from their customers and members of the Dorothy L. Sayers Society.

At the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2005, Edward performed his one-man play Pillar Talk about the fifth-century Syrian saint Simeon Stylites, the remains of whose pillar he had visited that year. He subsequently recorded a radio version of the play which will shortly be available for the first time on CD through Brainfood Audiobooks UK. In anticipation of the CD’s release, Edward has recorded a special interview with Brainfood, featuring questions elicited from their customers and members of the Dorothy L. Sayers Society.

Click on the media player to hear Edward’s recorded answers and follow the transcript below. KR

PART ONE

Question 1

Are readers given instructions on how to cope with a reading or is it their own decision how the material should be handled?

Answers to readers. The first question is Instructions to readers. By the way I’m trying to do this little recording in one take but if I were doing a voiceover, a fifteen-second voiceover, to a TV or radio ad, there might be up to three people behind the glass, not including the sound engineer. Four, including him, will have an opinion and they also are trying to second-guess what the client might want, who may not be there. An hour is routinely consumed to record many, many takes, alternative interpretations of mood and tone: ‘Could you be more jocular?’ ‘Could you be a touch faster?’ Even alternative wordings. Timing is done literally to the half-second. I could go on about the intensive work involved in recording fifteen seconds. A nine-hour audiobook would take years to read at that rate. Time is money. It is assumed that the chosen reader will hit the right tone and knows what she or he is doing. The producer follows the text, intervening if there is a misreading or a lack of clarity, rarely suggesting interpretation. It’s a very personal business reading a book; an imaginative and technically demanding exercise in absorption. What one tries to do is get right through the book, seamlessly, and of course the only stops tend to be for fluffs. One does occasionally, or even quite regularly, fluff.

Question 2

Here’s something I wonder about all these brilliant readers – do you have to like a character to read it well? If not, how do you read (or indeed act) a part empathetically if the character basically repels you?

Repellent characters. Usually the author wants his audience to be repelled to an extent. I’m thinking of that elderly clergyman the naive heroine in Middlemarch marries. I would revel in such a well-drawn character, and a great writer such as George Eliot, leads one to even the most flawed character’s point of view. How they view the world and other people, their obsessions and, since conflict is the essence of the drama of the book, part of that conflict, that tension, might be empathizing, at the same time as deploring and understanding a character.

Question 3

How many times do you have to read a book before you feel ready to read it well?

It depends. There is a story of a rather famous, distinguished and very good reader of audiobooks, who turned up at a studio with a neatly wrapped brown paper parcel under his arm, and the producer said to him: ‘Isn’t this a wonderful book?’ And the said actor, who shall be nameless, said: ‘So everybody tells me’ and began to open the parcel. Well, another story of somebody who was again an expert sight-reader, of course, got to the end of a book and realized – a revelation in the last chapter – that one character, should have had a foreign accent and hadn’t had a foreign accent all the way through the book so they had to go back and re-record every little utterance of this character throughout the book.

Question 4

Please can you tell me which was the last Lord Peter Wimsey book you performed? And are there any plans for you to read The Late Scholar?

Now let me see, the last Wimsey audiobook I did was The Attenbury Emeralds. Those were the days; I was recording it near Goodge Street, over four days, until about 5 pm, and then walking from there to near the Aldwych, buying a nutritious sandwich, and napping in my dressing room at the Duchess Theatre before performing in the musical The Fantasticks. Then waking next morning to repeat the process. Paton Walsh’s segue into the world of 1951 seemed to me seamless and fascinatingly detailed and the maturing of the relationship with Harriet quite perfect, and Bunter too. I read a section of the book at the launch, actually in the House of Lords, well in an adjacent reception room, in the Place of Westminster overlooking the Thames. The Dorothy L. Sayers Society was there in force and Norma Major. I’d been invited by the Majors to No.10 some years before on the strength of Lord Peter … and me a commoner.

Now let me see, the last Wimsey audiobook I did was The Attenbury Emeralds. Those were the days; I was recording it near Goodge Street, over four days, until about 5 pm, and then walking from there to near the Aldwych, buying a nutritious sandwich, and napping in my dressing room at the Duchess Theatre before performing in the musical The Fantasticks. Then waking next morning to repeat the process. Paton Walsh’s segue into the world of 1951 seemed to me seamless and fascinatingly detailed and the maturing of the relationship with Harriet quite perfect, and Bunter too. I read a section of the book at the launch, actually in the House of Lords, well in an adjacent reception room, in the Place of Westminster overlooking the Thames. The Dorothy L. Sayers Society was there in force and Norma Major. I’d been invited by the Majors to No.10 some years before on the strength of Lord Peter … and me a commoner.

Are there any plans for me to record The Late Scholar. I’m afraid it’s too late. No, my last Wimsey book was The Attenbury Emeralds; I bowed out with that. Wimsey, after all, is immortal but, with me, it’s a case of tempus fugit.

PART TWO

Question 5

My favourite audiobook of yours is Gaudy Night. According to David [Yelland of Brainfood Audiobooks] it was only ever released as an abridged version. Is there an unabridged version out there?

I didn’t record an unabridged version of Gaudy Night, though the novel, when I read it prior to doing the television version struck me as by far the most fully achieved and novelistic of the Harriet Vane/Peter Wimsey stories. I’m afraid the producer of the television versions didn’t have the same feeling about that particular book and so it rather gets short shrift, I feel, televisually.

I didn’t record an unabridged version of Gaudy Night, though the novel, when I read it prior to doing the television version struck me as by far the most fully achieved and novelistic of the Harriet Vane/Peter Wimsey stories. I’m afraid the producer of the television versions didn’t have the same feeling about that particular book and so it rather gets short shrift, I feel, televisually.

Question 6

Ian Carmichael was well known as Lord Peter Wimsey from the TV productions of the 1970s. How did it feel to walk into those shoes?

I’ve been asked what I felt about stepping into Ian Carmichael’s shoes as Wimsey. It really never occurred to me. I was much too preoccupied with trying to step into Lord Peter’s shoes. One makes the direct beeline for the character. After all, think about it: James Burbage played all the leading parts of Shakespeare. Not only that but he had Shakespeare to advise and direct him. Now, if one thought of stepping into Burbage’s shoes or Sir This or Sir That’s shoes who played Lear or Prospero or Hamlet, where would you be? No, the actor, be he ever so humble, needs a copper-plated, brass-fronted ego of confidence, laced with the kind of doubt that comes from nightmares about being weighed in the balance and found wanting. It’s a combination that’s devoutly to be wished.

Question 7

Any ‘audio’ anecdotes regarding the NT/Olivier times?

Anecdotes. National Theatre anecdotes. Well, of course, I’m in my anecdotage so I’ve stacks of them and there are some of them in my book, Slim Chances. I hope they pass for deathless prose, that they’re woven into the narrative properly, so they don’t stick out like so much theatrical gossip.

Anecdotes. National Theatre anecdotes. Well, of course, I’m in my anecdotage so I’ve stacks of them and there are some of them in my book, Slim Chances. I hope they pass for deathless prose, that they’re woven into the narrative properly, so they don’t stick out like so much theatrical gossip.

A good anecdote should have a kernel of something fascinating about a particular era or a particular character.

I’ve got one I can share with you now about the National Theatre canteen in the Old Vic, in the old days. Well, of course, it depends which old days you’re talking about, but the early 60s. Laurence Olivier’s dressing room was immediately above this basement canteen. It was a steamy place, meat and two veg were served, and sausages were on the menu. Olivier liked those and sometimes he would come to join the queue, and order his sausages, and you hoped, or dreaded, that he would sit at your table.

On one such occasion the conversation at the table turned to the acting of Shakespeare, the speaking of Shakespeare, and Olivier said that, as a young actor, his speaking of Shakespeare was vilified by the critics because he didn’t speak it poetically. He said the trouble was, I wouldn’t ‘sing’.

That was about all he said. Well, we were playing Othello, at the time, I was playing a tiny, tiny one-line part, and he was giving forth his Othello, and of course … well, I won’t say he sang it, but all I can say now is that when I see Othello again, with somebody else playing the part, I sometimes feel they’re ‘doing the wrong tune’. He didn’t sing it, he spoke it magnificently, but there is a sort of sense of song, a sense of transcending, well Shakespeare isn’t just idiomatic, everyday speech like you and me, is it? I can’t pretend it is. One has to make it sound vital and believable, the only way the character could speak, and, if you can’t cross that barrier into hyperbole and effective speech – ‘rhetoric’ is only another word for effective speech and Shakespeare’s characters, in extremis, do speak very effectively and passionately. I’ll stop now before I get too anecdotal.

That was about all he said. Well, we were playing Othello, at the time, I was playing a tiny, tiny one-line part, and he was giving forth his Othello, and of course … well, I won’t say he sang it, but all I can say now is that when I see Othello again, with somebody else playing the part, I sometimes feel they’re ‘doing the wrong tune’. He didn’t sing it, he spoke it magnificently, but there is a sort of sense of song, a sense of transcending, well Shakespeare isn’t just idiomatic, everyday speech like you and me, is it? I can’t pretend it is. One has to make it sound vital and believable, the only way the character could speak, and, if you can’t cross that barrier into hyperbole and effective speech – ‘rhetoric’ is only another word for effective speech and Shakespeare’s characters, in extremis, do speak very effectively and passionately. I’ll stop now before I get too anecdotal.

Question 8

It has been mentioned that you will be releasing a new audio title in the near future. Please can you tell us where the idea for Pillar Talk came from?

Where did Pillar Talk come from? Where it went to might be as much to the point. The chaos and carnage which has overtaken Syria since I wrote the play seemed to invalidate my portrait of Simeon sitting, for the most part, quietly on top of his pillar. I sought out a copy of a play about the saint I faintly remembered being done at my school by some other boys. I thought perhaps it might furnish me with a part. I’ve described what I do remember of the 1951 or 2 school production, my reactions on reading the script, and the idea that I might go one better, and one better again in the audio version, in the new introduction to the CD. In a way, mine is an impossible premise – no pilgrim actually visits Simeon. We seem to spend a day with him, fifty feet high. Audio has the best scenery, though entirely dependent on the imaginative capacity of each listener. It is to be hoped that the result transcends the mere attempt to write an effective part for myself, and doesn’t suffer from owing very little to the actual nature of the outlandish historical figure we glimpse through the scant accounts of his life. I had fun adapting it to audio; it seems to me, dare I say, to take to the air rather well.

PART THREE

Question 9

You have lots of audiobooks on the Brainfood website. Which one is the most memorable and which one was the most enjoyable? What is your favourite audiobook?

Well I don’t do favourites really but I do like listening to books being read on the radio, BBC radio. Talking of the BBC, they made a recording of not a book but a play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, back in the day. It wasn’t the original cast – I’d left the company by then – but there was an issue of the cassette, which you can’t get for love nor money now, I understand. However, if you are a certain documented person that can go to the British Library, and look into their archives, you can hear one better than that; you can hear a live recording of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead from the stage of the Old Vic theatre in 1967. You can hear the traffic faintly through the dock doors. You can hear the audience laugh – ah! that’s music for my ears of course – and you can hear the sound of the electric curtain. Do any of you remember that electric curtain, going up in the dark. Yes, that’s a particularly fond memory.

Well I don’t do favourites really but I do like listening to books being read on the radio, BBC radio. Talking of the BBC, they made a recording of not a book but a play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, back in the day. It wasn’t the original cast – I’d left the company by then – but there was an issue of the cassette, which you can’t get for love nor money now, I understand. However, if you are a certain documented person that can go to the British Library, and look into their archives, you can hear one better than that; you can hear a live recording of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead from the stage of the Old Vic theatre in 1967. You can hear the traffic faintly through the dock doors. You can hear the audience laugh – ah! that’s music for my ears of course – and you can hear the sound of the electric curtain. Do any of you remember that electric curtain, going up in the dark. Yes, that’s a particularly fond memory.

Where Angels Fear to Tread [by E. M. Forster]. There is in that book a wonderful scene describing a provincial opera performance in a small town (San Gimignano possibly) and it’s a tawdry event but it’s very spirited, being Italian, and of course it’s written with a passionate attention to detail and a sort of onward momentum. Those passages in books are very splendid to read; you fluff less times because you’re on a sort of emotional umbilical cord with the actual spirit of the author. A similar passage, but totally different and very English, but a similar sense of achievement and brio, is in The Go-Between, the cricket scene in L. P. Hartley’s Go-Between. Marvellous! The extraordinary atmosphere in Oscar Wilde’s famous Dorian Gray is constantly a wonder. And I once did a 2-CD version of Tolstoy’s War and Peace. A ridiculous abridgement, of course, and a young person, who heard it a year or two ago, said to me: ‘What an extraordinary “period” reading it was’ I did. Think about that! Ah well, each to his own.

Somebody told me that they’d worn out their copy of Muriel Spark’s Memento Mori, they liked listening to all the different voices of the characters so much, and I don’t believe it’s been transferred to CD, but Memento Mori was another wonderful chance to ‘show-off’, I suppose, doing a wonderful collection of contrasting characters. I haven’t heard it for years.

Question 10

You are married to the well-known actress Emily Richard. Have you ever released any audio productions with your wife?

Emily and I recorded a double CD of prose and poetry. David might have plans to reissue it, I’m told.

Question 11

Audiobooks are a very personal way of experiencing a story. How do you approach recording an audiobook?

As for approaching a book, an audiobook, it’s a question of entering into a state of being, if that doesn’t sound too hifalutin. Several states of course. Sight-reading some people do well, even on first sight, and even if that first sight is in the studio. I like to read the book at least twice beforehand but one can never prepare enough; there isn’t the time to get oneself into a state where one can anticipate everything that’s coming up and give a planned performance. So, it’s essentially an improvisation, guided by an author who may have slaved over, and endlessly revised, a text for the reader to absorb without too much effort. Effort, consequently, is the last thing an audiobook needs to show. And that needs … effort.

* Brainfood Audiobooks UK stock a number of Edward’s audio performances on CD and cassette, including the audiobook of his autobiography Slim Chances with Additions and Afterthoughts.

-

CATEGORIES

Uncategorized -

DATE

November 6, 2017 -

COMMENTS

1 Comment

One thought on “AUDIO INTERVIEW”