MORE MATTER FOR A MARCH MORNING

Odd that on my last ‘Bard Blog’ day – I usually start thinking about the blog on Friday – I should have met someone who remembered my Hamlet; a tall order because, although two productions of Hamlet featuring me as the Prince were planned, one at the Mermaid Theatre, the other by the British Council to take place against the Phoenician ruins at Baalbek, both were, for different reasons, cancelled. Quite another infinitely sad story (for me at the time), but Bernard Miles had a financial crisis and took the opportunity to stage a small-cast Noël Coward revue, Cowardy Custard, which was much cheaper than Hamlet and did bravely at the box office, whilst the Bolshoi Ballet offered their services free to Baalbek for whatever dark Soviet cultural motive. So I never played nor even rehearsed the part. And yet …

There is a pet shop in Kilburn Market where I went to buy a new harness for Bean this afternoon, dropping in at the same time to an unlikely art gallery in nearby Willesden Lane, just off Kilburn High Road, that sells a rather interesting clutter of paintings. It was there that the elderly gent, whom I asked about one of the paintings, told me we’d been in the army together in basic and trade training, circa 1957, and used to go drinking together. Indeed I recalled the brief moment dimly when, late at night, feeling euphoric and unaccustomed to being drunk, I mounted some concrete block on the way back to Blackdown Camp and held forth. I’d have thought it might have been in raucous song, but I am assured it was ‘O, that this too too solid flesh would melt’.

Pvt. Petherbridge, 2nd from left on front row

Now follows the serious note on which I had intended to open this blog:

When I am absorbed in reading, a second self takes over, a self which thinks and feels for me. Withdrawn in some recess of myself, do I then silently witness this dispossession? Do I derive from it some comfort, or, on the contrary, a kind of anguish? However that may be, someone else holds the centre of the stage, and the question which imposes itself, which I am absolutely obliged to ask myself, is this: ‘Who is the usurper who occupies the forefront? Who is this mind who alone all by himself fills my consciousness and who, when I say I, is indeed that I?’ (Georges Poulet, Phenomenology of Reading)

This second self, whoever it may be, it seems to me, chimes in with the beginning of the actor’s work on a part. But even when I read, for example, Stanislavski explaining in 1929 his ideas for a production of Othello, and note with amazement combined with amusement the second sentence of his instructions: ‘A few words about the gondola and its movements across the stage’ (there follows an intricate description of how to produce a realistic effect of a gondola on water) – even here Poulet’s second self partially takes over; perhaps I even become my idea of Stanislavski as I enter his world and the world of his proposed production of Othello, though a third self remembers, or even is, my young self playing a Senate Officer at the Old Vic in 1964, and yet another I remembers Laurence Olivier at that time, and still another empathizes so closely with Olivier that Olivier seems almost to be one of my selves, and I haven’t even shifted in my armchair!

On the stage, whatever one’s reading or rehearsal process has been, there is only room for two selves, which must ‘act’ as one. As Gielgud observed:

[The actor] has the double task of both living in his role and of judging his own effects in relation to his fellow players and the audience, so as to present an apparently spontaneous, living pattern, carefully devised beforehand, but capable of infinite shades of colour and tempo, and bound to vary slightly at every performance. The actor, after all is a kind of conjurer.

Gielgud, writing about Richard II, seems, in two and a half pages, to say all that needs to be said about acting Shakespeare. Here is a sample:

In these later scenes the subtleties of his speeches are capable of endless shades and nuances, but, as is nearly always the case in Shakespeare, the actor’s vocal efforts must be contrived within the framework of the verse and not outside it. Too many pauses and striking variations of tempo will tend to hold up the action disastrously and so ruin the pattern and symmetry of the verse.

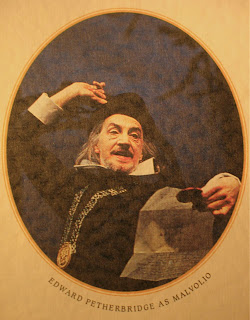

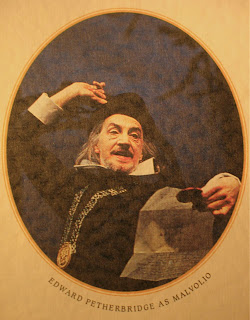

Let me tell you about two Malvolios. One of them is a real person whom I have seen on two fairly recent occasions. The other I was aware of some years ago, uncannily real too – the man himself – whilst in the early stages of rehearsing to play Malvolio for the RSC in 1996. I sensed he was there just inside the very fabric of the page of the script I was holding; if only I could somehow bridge the ineffable gap so as to walk by his side or take his hand.

Malvolio’s Stratford-upon-Avon Matinee.

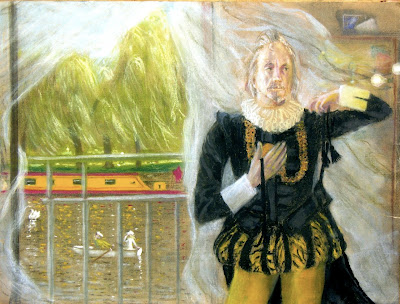

Self-portrait, pastel on paper, 1996

Malvolio is quite a small part as leading parts go – five scenes I think. And in the ‘ring scene’ he hardly says anything, but everyone who has seen the play remembers him running on to catch up with Viola to ‘return’ the ring, in spite of the fact that, as soon as Malvolio is gone, Viola begins her soliloquy (‘I left no ring with her: what means this lady?’), another of her rhapsodic and comic outpourings. What a talented boy actor the Bankside company must have had that Shakespeare was emboldened to write such a golden part!

The base metal of Malvolio’s part is successfully subjected to Shakespeare’s alchemy. When his pathetic little fantasy world collapses the audience is finally moved; I still remember being surprised by the sob I uttered when I watched Desmond Barrit, my forebear in the part, say, ‘I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you.’

Malvolio; not as heroic as he thought …

But it was a curious experience, sensing, for a moment or two, Malvolio as a real presence hovering inside the page of my well-thumbed Arden edition. I couldn’t have told you what he looked like, and at this distance the nebulous potency of the experience is something I can relate but not feel again. In any case, I had to get on with the business of being him myself.

I can tell you what the other real-life Malvolio looks like. His inner life may bear no resemblance whatever to the famous steward, but I can vouch that, for me, the outward man resembles him uncannily – that word again. Last year at Paul Scofield’s memorial service he performed the selfsame ceremonial duty I’d seen him execute impeccably before, leading the Mayor of Westminster to her pew in St Margaret’s Church, and then, with sustained dignity, making himself scarce somewhere behind the organ until he was required to re-emerge and escort her out. He seemed to embody the mystery of the office he served in a way that the Mayor herself did not; she was a lady in a hat and suit, wearing a chain that you might not notice, who walked in an unassuming way to her place, and might have been glad to have got her entrance over and done with – only he gave the event of her arrival due portent.

We could not but admire his gait and his carriage, the cut of his splendid morning coat, the way he held the piece of wood topped with a bit of gold trumpery. His expression was as inscrutable as the most arcane ceremony you can imagine and yet, as true British subjects, he made us all momentarily conscious of our position, our rank. It was the performance of a non-commissioned officer, and if he had fallen prey to a plot to make him think the Mayor was in love with him – and, better still, if she had been a young princess, and he convinced he was destined for high office and title – 400 years of creeping egalitarianism would have slipped away in derisive laughter.

The Stage said of my Malvolio: ‘Petherbridge’s letter scene with deliciously inventive dog turd business is the stuff of which the greatest mime performances are made.’ Actually it was a peacock dropping! As I spied the letter, I had to stride over a bit of knot garden and my leading heel slipped forward from under me on the aforementioned peacock dropping – it was a formal garden, you understand. On a good night my hat fell off, and I recovered by wiping my shoe clean on a crisp little bed of plastic cropped greenery before picking up the letter. I also had a green umbrella – don’t Stanislavski and Dickens both have things to say about these aids to character? Anyway, at one point, I became so absorbed in the letter that I sat on a garden bench and a nice Freudian effect happened. Inadvertently I sat on the handle of the umbrella and, with a startling sea-saw jerk, the rest of the instrument twanged horizontally erect, if you see what I mean.

This photo reminds me that in Vienna, which we played after Woking, in his deluded ‘privacy’ of the letter scene, Malvolio was so excited about the contents of the letter that he showed the handwriting on the missive to several people on the front row.

I once performed Richard II’s prison soliloquy and, although I had many years before experienced periods of solitary confinement in three different prisons as a conscientious objector, it occurs to me now that I never brought that experience to bear on King Richard’s speech. But actually Richard is not alone. Like the comically deluded steward, the tragic king has his confidantes in the audience; thus the magical tension created by theatrical paradox. Richard begins by explaining to the audience what he was doing before the scene began:

I have been studying how I may compare

This prison where I live unto the world;

And, for because the world is populous,

And here is not a creature but myself,

I cannot do it. yet I’ll hammer it out. (V.v.1-5)

And so he does, directly addressing the large audience, drawing the crowd of auditors into his confidence and solitude and the experience of being a king, reduced from Divine Right to no rights at all, and, though he does not know it, about to be murdered.

David William as Richard II in the BBC TV series

An Age of Kings, 1960

The pretext, or context, for doing the speech lay in my show Defending Jeffrey … ? at the West Yorkshire Playhouse in 2001. Returning to Stanislavski – I don’t remember, as I say, using the sense memory of my own imprisonment (a matter of weeks, as it happened, after that impromptu Hamlet at Blackdown Camp). ‘Someone else’ held the centre of the stage and I ‘lived’ through the words the Bard had furnished to King Richard. My own ‘lower ranks’ experience in a guardroom cell, Her Majesty’s Prisons at Winchester and Wormwood Scrubs paled to insignificance. In any case, though I had disobeyed Queen’s Regulations in 1957 by refusing to wear uniform, I was within my common rights as a subject, and after three months was granted a civil tribunal hearing in a building in London’s Ebury Street, not drowned in a malmsey-butt like royal Richard.

A page from a First World War conscientious objector’s prison

autograph book. I found it in the history bookshop in Great Newport Street.

Ironically I was advised not to speak at my tribunal; a lawyer read a statement I had written days before on prison notepaper. I wonder how related to me was his ‘Someone Else’ who, for a few moments, held centre stage in that upper room, tucked just behind Buckingham Palace.

8 thoughts on “MORE MATTER FOR A MARCH MORNING”