A NUANCE OF UNDERSTANDING

Helen: The spotlight was on you and you alone, and you weren’t even young men; you were children. …

David: All right, then. Go on. What did we do with this spotlight?

Helen: You did what any child would do. You danced in it.

(Terence Rattigan, After the Dance)

That special performance of the Afghanistan plays, The Great Game, which I was talking about last week, was described by General Sir David Richards, Chief of the General Staff, as ‘fascinating, entertaining and historically accurate of Britain’s involvement in Afghanistan since 1840. … Nothing learnt in the classroom will have the same subliminal effect as this. It is crucial that all of us out there have a more nuanced understanding of the historical background that got us to this point.’ (The Times, 3 August)

Unfortunately my great nephew was not among the fifteen officer cadets from Sandhurst who attended the day-long performance at the Tricycle. The theory of fifteen degrees of separation comes pretty close though, and who knows how much closer than a mere fifteen degrees it sometimes comes without our knowing. However, a few days after my own three-evening induction course in the ‘nuanced understanding’ the general wrote of, I was at the National Theatre for a Saturday matinée of Terence Rattigan’s second West End success, After the Dance, rarely staged since its premiere in the summer of 1939. The play is both a bleak indictment of and an elegy for the Bright Young Things, a generation of whom G. B. Stern observed, ‘They were suffering not from shell-shock but from the echo of shell-shock.’ Rattigan, in my very young day, was the apotheosis of the West End, and I can tell you that West End theatre felt further away this last Saturday from Kilburn High Road than its Tricycle Theatre had seemed from Afghanistan the week before. Such is the theatre’s ability to create a potent sense of an era, a place, another world.

Nancy Carroll and Benedict Cumberbatch in After the Dance.

Photo by Johan Persson

As it happens, I have, this past week, been preoccupied by the West End, feeling I must revise one of the early chapters in my book, an essay entitled ‘Keeping it West End’ in ironic homage to the company manager of Worthing’s weekly rep where, in 1957, I was appearing in The Case of the Frightened Lady. Over a drink in the bar of the Connaught Theatre, after the Monday opening night, Melville Gillam issued what I had been warned was his habitual injunction: ‘Keep it West End.’ I knew then just how far away we were from getting it West End – let alone keeping it there!

But what is, or rather was, the essence of West End theatre? Noël Coward was once addressed about it at a party: ‘Oh, Noël, the West End isn’t what it was!’ ‘It isn’t’, The Master replied, ‘but then – it never was.’

Watching Rattigan’s play was for me spellbinding, the theatrical equivalent of being absorbed in a good book that one doesn’t want to end; and if it was not an utterly perfect performance, it seemed to have all the verities on so many levels – in the writing, staging and acting – the sort of theatrical quality of spell I almost imagined I had not witnessed, and had been missing, since I saw the pre-West End tour of Rattigan’s Separate Tables in Leeds as a teenager in 1954 – with Margaret Leighton and Eric Portman in the leading roles.

Afterwards, I was astonished to spot a familiar name on the cover of a newly reissued Rattigan biography on display in the NT bookshop: Michael Darlow was the author. I knew him, as he had been two years ahead of me at Esmé Church’s Northern Theatre School in Bradford. His substantial book (over 500 pages) is so far fascinating. A surprising contribution comes from, of all dramatists, the radical playwright David Rudkin:

I think Rattigan is not at all the commercial middlebrow dramatist his image suggests but someone peculiarly haunting and oblique who certainly speaks to me with resonance of existential bleakness and irresoluble carnal solitude.

Terence Rattigan, 1949.

Photo by John Gay. National Portrait Gallery

Since Saturday I have talked to one actress who found the play predictable and the performances somewhat pedestrian. I also bumped into a contemporary of mine, a director, who was in a very bad mood about it: ‘Most of the actors have no idea of The West End Style!’ Was there ever such a thing? I am going to attempt to anatomize that question in my aforementioned chapter. Meanwhile, here is my more or less finished pastel showing the inside of one West End theatre (the Playhouse to be exact), which you saw in embryo last week.

Dreamboats and Petticoats (Click image to enlarge it)

Postscript

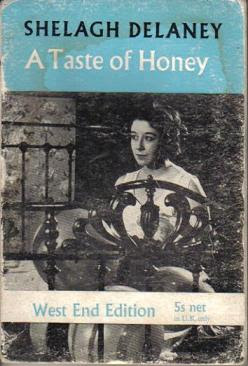

In 1958, an eighteen-year-old Salford girl took two weeks off work to convert a novel she was trying to write into a play, partly because she was so disgusted with Rattigan’s Variation on a Theme which she had seen on tour in Manchester. For her, Rattigan and the ‘West End Style’ symbolized ‘safe, sheltered, cultured lives in charming surroundings – not life as the majority of ordinary people knew it. I had strong ideas about what I wanted to see in the theatre. … Usually North Country people are shown as gormless whereas in actual fact they are very alive and cynical.’ Her play was produced by Joan Littlewood in the East End in May 1958. The following year Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey transferred to Wyndham’s Theatre, where it became a West End hit.

Oh, Noël!

A scene from the 1961 film adaptation of A Taste of Honey

3 thoughts on “A NUANCE OF UNDERSTANDING”