If this is not enchantment then where is it to be found?

J. B. Priestley

Dreamboats and Petticoats, Playhouse, London, 2010

The Roses and the Bear, Northern Children’s Theatre, 1956

Fifty-four years separate the two theatrical events depicted here. The more sober, dramatic scene took place at a dress rehearsal of a children’s play I did when I was nineteen. I got the idea to turn a fuzzy black-and-white photograph somebody took of us rehearsing the last scene into a colour painting, showing not only the stage, but also the kind of theatre we often played in, and the rows of children to whom we played. The scale is a little exaggerated, the actors look large and the children small, but that may be how it seemed at the time. Our faces on the canvas are no bigger than half the size of my little fingernail, and I don’t have the technique to do features accurately at that size. Perhaps the figure on the right is the one most successfully depicted in the approximately on purpose style of the Camden Town School. But I remember them all in high detail as people, having gone through two years training with them at the Northern Theatre School in Chapel Street, Bradford, and toured the big Moss Empires variety theatres in the North and Midlands for the best part of a year with the Northern Children’s Theatre production of The Roses and The Bear, a play by William Baines. In Bradford alone more than 5,000 children saw the play.

In the painting, I am centre stage with hand outstretched and my first wife is in kingfisher green, playing a pageboy. She had a beautiful little tune composed for her to whistle whilst she guarded Rose White and Rose Red in the forest at night; it was never heard because the Bear appeared and the children’s screams astonished us all at the first performance.

I have promised myself to portray in pastel a scene from the second show we toured, The Dancing Master’s Kit, to form a third piece in my Sickert-inspired collection.

The Northern Children’s Theatre was the pride and joy of our principal Esmé Church; she founded it in 1946, using her final-year students. Esmé had the status of a minor goddess in Chapel Street, and no wonder: she had been a West End and classical actress for years – not a star, but she had directed the famous Edith Evans-Michael Redgrave As You Like It the year I was born; acted with and directed Laurence Olivier; and run the Old Vic School of Acting. She’d toured the North during the war when the Old Vic Company was avoiding the bombs and taking the classics to remote industrial and mining towns. Peace came, she arrived at a certain age and, with her designer Molly McArthur, bought a part-Elizabethan, part-Georgian farmhouse in the dales outside Bradford on an old Roman road. Amazingly Esmé assumed the professional directorship of the amateur Civic Playhouse, and from this connection developed the Theatre School.

Esmé Church

A day of art! I finished the painting this afternoon (it needs a tidge more work) and then went to see The Illusionist, the brilliant animated film directed by Sylvain Chomet and based on an unproduced script that Jacques Tati had written in 1956 (the year I was touring in The Roses and the Bear). It is the tale of a magician, one of the dying breed of music-hall turns.

A scene from The Illusionist

I worked on the same bill with Tati once, on a TV programme, and he was a wonderful live comic turn. Oddly, I first saw him on film in Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday, when I was still a drama student – it was at the Civic which was also an art-house cinema.

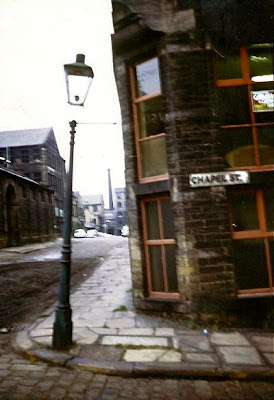

This is a picture I took of Chapel Street, my Mecca in those days and the street to which we returned our touring scenery. It had at least one of its gas lamps at an angle that even Charlie Chaplin might have thought exaggerated until handled by one his villainous roughs. It is perhaps not a thoroughfare you would associate with art, or even with roses and bears and gilded theatres and enchantment, but that is where I found them.

Postscript

I should add a few words about where I saw The Illusionist on Sunday night; it was in the Hampstead Everyman Cinema, a building that started life in the late nineteenth century as a drill hall for the Hampstead Rifles. By the 1920s it had become what we would now call a fringe theatre, and Noël Coward, just short of his twenty-fifth birthday, had his first hit there in 1924 – The Vortex. He described the basement dressing-room area with its frowsy comfortable sofa, and the auditorium with its iron-girdered timber roof: ‘The whole place was carpeted throughout with coconut matting and a pervasive air of artistic endeavour.’

Circa 1920 and today

I missed the chance to see the recent revival of The Vortex with, I gather, Felicity Kendal and Dan Stevens being seeringly consummate as mother and son. ‘Any production of Coward that has you thinking in all seriousness of Sophocles and Strindberg [which sounds artistic enough] has clearly achieved something pretty remarkable’, raved Christopher Hart in The Sunday Times. ‘We do not need this filth in the West End’, fulminated Gerald Du Maurier in 1924, probably helping to ensure a long run for the transfer. It was Du Maurier, a Hampstead resident, who opened the Everyman Cinema in 1933.

Lilian Braithwaite and Coward in The Vortex

There are two screens at the Everyman, one in the basement and another under the iron and timber roof. Now the whole place is carpeted throughout in Wilton one notices, before sinking into immaculate scarlet sofas and having drinks and snacks brought to one’s little table.

I counted, amongst the lengthy credits for The Illusionist, thirty-two names under the heading ‘Ink and Paint’ alone! Go to this film just to see how Edinburgh is depicted, for the amazing flight over the city, the poignancy of Tati’s gentle story: for Artistic Endeavour triumphant in fact.

5 thoughts on “YOUNG ILLUSIONISTS”