REBELS, POETS AND A QUARE FELLOW

Yet there are times when a deeper need enters, when we want the poem to be not only pleasurably right but compellingly wise, not only a surprising variation played upon the world, but a retuning of the world itself.

Seamus Heaney, ‘Crediting Poetry’, Nobel Lecture, 1995

In celebration of St Patrick’s Day, a preview of our (Kathleen’s and my) book, featuring just a few of West Hampstead’s notable Irish connections.

The

Dandy of the War of Independence

Dandy of the War of Independence

|

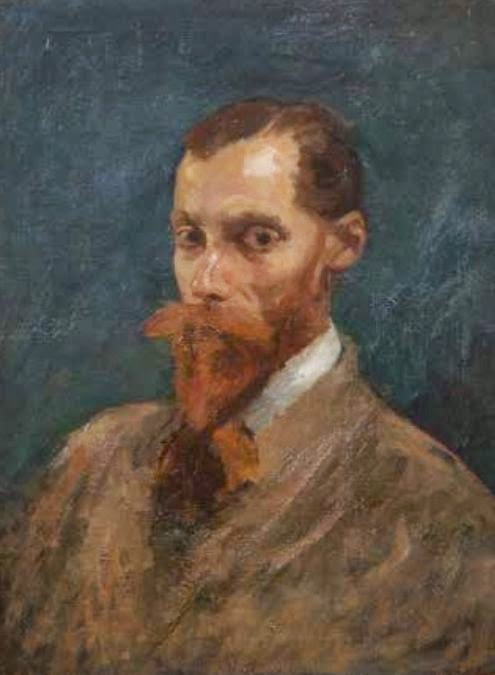

| Portrait of Figgis by Estella Frances Solomons |

Long a home for mavericks as well as movers

and shakers, West Hampstead can boast among its former residents a Russian

Revolutionary, a Confederate naval hero of the American Civil War, and a

defender of the Eureka Stockade miners. It is also the final resting place of Edward Darrell Figgis (1882-1925), poet,

novelist, playwright, Sinn Féin activist and independent parliamentarian in the

Irish Free State.

and shakers, West Hampstead can boast among its former residents a Russian

Revolutionary, a Confederate naval hero of the American Civil War, and a

defender of the Eureka Stockade miners. It is also the final resting place of Edward Darrell Figgis (1882-1925), poet,

novelist, playwright, Sinn Féin activist and independent parliamentarian in the

Irish Free State.

‘His life consists of the stuff of which

fictions and films are made,’ said one observer who studied his short life and

dramatic career. When Michael Collins signed the new Irish constitution in the

Shelbourne Hotel in 1922, the document was largely the work of Figgis. That

same year Figgis was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

fictions and films are made,’ said one observer who studied his short life and

dramatic career. When Michael Collins signed the new Irish constitution in the

Shelbourne Hotel in 1922, the document was largely the work of Figgis. That

same year Figgis was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Born in Rathmines, Dublin, not far

from the home of his contemporary James Joyce, he spent his formative years in

India where his father owned a tea plantation, and as a young man he became

immersed in London bohemia before returning to Ireland and joining the newly

formed Irish Volunteers. Figgis had been the main organizer of the famous arms

shipment that was landed at Howth Pier in 1914 and, although he did not take

part in the Easter Rising of 1916, he was one of hundreds of Sinn Féin

supporters who were rounded up in its aftermath. He was interned in Reading

Gaol and recounted his experiences in his book A Chronicle of Jails.

from the home of his contemporary James Joyce, he spent his formative years in

India where his father owned a tea plantation, and as a young man he became

immersed in London bohemia before returning to Ireland and joining the newly

formed Irish Volunteers. Figgis had been the main organizer of the famous arms

shipment that was landed at Howth Pier in 1914 and, although he did not take

part in the Easter Rising of 1916, he was one of hundreds of Sinn Féin

supporters who were rounded up in its aftermath. He was interned in Reading

Gaol and recounted his experiences in his book A Chronicle of Jails.

|

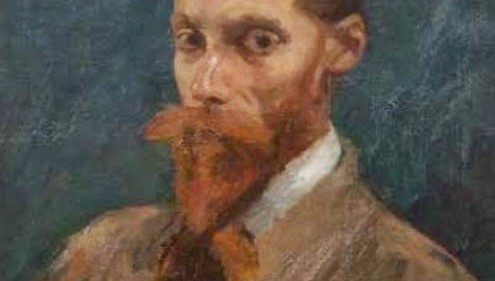

| Photo: RTÉ Stills Library |

A dandified and fiercely independent

character, Figgis eventually had a serious falling out with Michael Collins. On

13 June 1922, a group of armed men broke into his Dublin flat and in a strange

ritual cut off half his ginger beard in which he had always taken inordinate

pride. A turbulent private life, mired in scandal, led him to take his own life

in 1925. The location of the grave of this founding father of the Irish Free

State was lost for over eighty years and rediscovered in West Hampstead as

recently as 2008.

character, Figgis eventually had a serious falling out with Michael Collins. On

13 June 1922, a group of armed men broke into his Dublin flat and in a strange

ritual cut off half his ginger beard in which he had always taken inordinate

pride. A turbulent private life, mired in scandal, led him to take his own life

in 1925. The location of the grave of this founding father of the Irish Free

State was lost for over eighty years and rediscovered in West Hampstead as

recently as 2008.

|

| Figgis’s grave in Hampstead Cemetery, Fortune Green |

Dublin’s

Answer to Gertrude Stein

Answer to Gertrude Stein

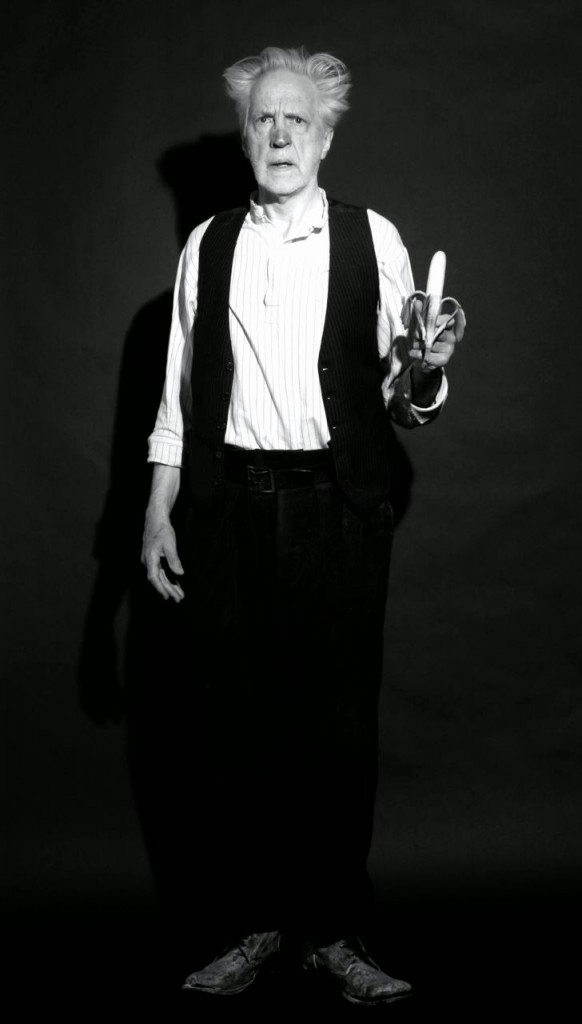

More of a cultural revolutionary, the sculptor,

stage designer and novelist Desmond MacNamara

(1918-2008) lived in a flat at 1 Woodchurch Road, West Hampstead from 1957

until his death. The house had been built by the Victorian painter John Seymour

Lucas, who was also Henry Irving’s costume designer. Early in his career, MacNamara

had worked as prop and costume designer for the film of Laurence Olivier’s Henry V. Before his move to London, MacNamara

had been known as Dublin’s answer to Gertrude Stein, running a non-stop salon in his sculptor’s studio on Grafton Street. In Paris he met Samuel Beckett when

the two of them helped the young sculptor, Hilary Heron, who had been injured

in a motorcycle accident.

stage designer and novelist Desmond MacNamara

(1918-2008) lived in a flat at 1 Woodchurch Road, West Hampstead from 1957

until his death. The house had been built by the Victorian painter John Seymour

Lucas, who was also Henry Irving’s costume designer. Early in his career, MacNamara

had worked as prop and costume designer for the film of Laurence Olivier’s Henry V. Before his move to London, MacNamara

had been known as Dublin’s answer to Gertrude Stein, running a non-stop salon in his sculptor’s studio on Grafton Street. In Paris he met Samuel Beckett when

the two of them helped the young sculptor, Hilary Heron, who had been injured

in a motorcycle accident.

|

| Portrait of Brendan Behan by Ida Kar, 1959. NPG |

MacNamara’s flat in Woodchurch Road was

packed to the groaning Pompeian-red ceiling with artworks, masks, books, and

other memorabilia. His mantelpiece housed a life-size bronze bust he made of his

best friend, playwright Brendan Behan. The two had met as teenagers on a

Spanish Civil War demonstration and Behan often stayed with MacNamara in West

Hampstead, including the time Behan was ejected from Wyndham’s Theatre for

drunkenly interrupting a performance of his own play The Hostage in June 1959.

packed to the groaning Pompeian-red ceiling with artworks, masks, books, and

other memorabilia. His mantelpiece housed a life-size bronze bust he made of his

best friend, playwright Brendan Behan. The two had met as teenagers on a

Spanish Civil War demonstration and Behan often stayed with MacNamara in West

Hampstead, including the time Behan was ejected from Wyndham’s Theatre for

drunkenly interrupting a performance of his own play The Hostage in June 1959.

Among MacNamara’s books were a biography of

Éamon de Valera, an acclaimed book on picture framing and another on puppetry.

Éamon de Valera, an acclaimed book on picture framing and another on puppetry.

|

| Desmond MacNamara |

In J. P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man (named one of the 100 Best Novels of the 20th

Century), MacNamara appears as ‘MacDoon. Small dancing figure. It is said his

eyes are like the crown jewels. A sharp red beard on his chin. A Leprauchaun

for sure. Can’t speak too loudly to Mac, else he might blow away.’ And in a

blurb for MacNamara’s Book of Intrusions,

Donleavy called MacNamara ‘the Einstein of Irish literature’.

Century), MacNamara appears as ‘MacDoon. Small dancing figure. It is said his

eyes are like the crown jewels. A sharp red beard on his chin. A Leprauchaun

for sure. Can’t speak too loudly to Mac, else he might blow away.’ And in a

blurb for MacNamara’s Book of Intrusions,

Donleavy called MacNamara ‘the Einstein of Irish literature’.

The

Bohemian’s Bohemian

Bohemian’s Bohemian

The West End actress Florence Farr

(1860-1917) was part of a legendary dinner party in Edwardian West Hampstead

and at the heart of the Irish Literary Theatre movement.

(1860-1917) was part of a legendary dinner party in Edwardian West Hampstead

and at the heart of the Irish Literary Theatre movement.

Named after Florence Nightingale, Farr was

a ‘First Wave’ Feminist, sometime mistress of Bernard Shaw, who wished to mould

her into his idealized vision of ‘The New Woman’, and a collaborator of W. B. Yeats,

Ezra Pound and Oscar Wilde. She was regarded as ‘the bohemian’s bohemian’ and

was the first woman in England to perform in Ibsen’s plays.

a ‘First Wave’ Feminist, sometime mistress of Bernard Shaw, who wished to mould

her into his idealized vision of ‘The New Woman’, and a collaborator of W. B. Yeats,

Ezra Pound and Oscar Wilde. She was regarded as ‘the bohemian’s bohemian’ and

was the first woman in England to perform in Ibsen’s plays.

|

| Farr as Louka in Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man |

Yeats made her stage manager of the Irish Literary Theatre and said of her: ‘She had three

great gifts, a tranquil beauty like that of Demeter’s image near the British

Museum reading room door, and an incomparable sense of rhythm and a beautiful

voice, the seeming natural expression of the image.’ Throughout the 1890s, he

used Farr’s voice as part of his quest to encourage the rebirth of spoken

poetry. They developed a theory of the music inherent in words, and Farr often

recited to a psaltery, assigning musical notations for the speaking voice. And

it was on one particular evening in 1909 at the home of editor Ernest Rhys, in

Hermitage Lane, West Hampstead, that Yeats and Farr transmitted their theories

to an audience that included Pound and D. H. Lawrence. Quite a good impressionist,

Lawrence’s favourite ‘turn’ was an imitation of Farr intoning the ‘Lake Isle of

Inisfree’ to the accompaniment of an imaginary psalter – something he first

witnessed in West Hampstead in 1909 – a party piece he was still doing in 1927.

great gifts, a tranquil beauty like that of Demeter’s image near the British

Museum reading room door, and an incomparable sense of rhythm and a beautiful

voice, the seeming natural expression of the image.’ Throughout the 1890s, he

used Farr’s voice as part of his quest to encourage the rebirth of spoken

poetry. They developed a theory of the music inherent in words, and Farr often

recited to a psaltery, assigning musical notations for the speaking voice. And

it was on one particular evening in 1909 at the home of editor Ernest Rhys, in

Hermitage Lane, West Hampstead, that Yeats and Farr transmitted their theories

to an audience that included Pound and D. H. Lawrence. Quite a good impressionist,

Lawrence’s favourite ‘turn’ was an imitation of Farr intoning the ‘Lake Isle of

Inisfree’ to the accompaniment of an imaginary psalter – something he first

witnessed in West Hampstead in 1909 – a party piece he was still doing in 1927.

|

| Farr with her psaltery harp in 1903, an instrument created for her by Arnold Dolmetsch |

Farr gave recitations to poets on a number

of occasions at Hermitage Lane after that. In 1909 she published The Music of Speech and her interest in

the interrelationship of music, poetry and the spoken language made her a

central figure in discussions of poetry during the years before the Great War.

of occasions at Hermitage Lane after that. In 1909 she published The Music of Speech and her interest in

the interrelationship of music, poetry and the spoken language made her a

central figure in discussions of poetry during the years before the Great War.

Farr, incidentally, is the subject of

Pound’s poem ‘Portrait d’une Femme’, which is supposed to have influenced or

precipitated ‘Portrait of a Lady’ by another sometime resident of West

Hampstead, T. S. Eliot.

Pound’s poem ‘Portrait d’une Femme’, which is supposed to have influenced or

precipitated ‘Portrait of a Lady’ by another sometime resident of West

Hampstead, T. S. Eliot.

(Research and text by Kathleen Riley)

One thought on “REBELS, POETS AND A QUARE FELLOW”